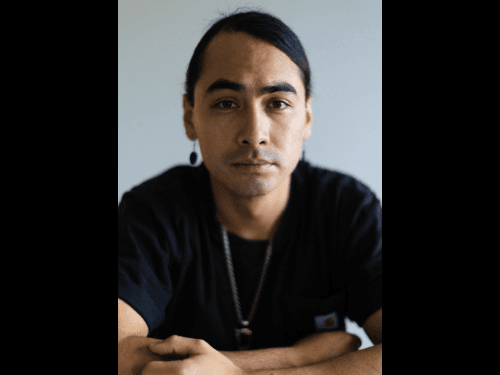

For this week’s MVP, we’re chatting with Julian Brave NoiseCat.

By Rosemary Counter

Filmmaker and activist Julian Brave NoiseCat made the history books this year: His debut documentary, Sugarcane, wowed audiences and won him Best Director at Sundance. Then the film scored an Academy Award nomination for best documentary—making NoiseCat the first North American Indigenous filmmaker to be nominated for an Oscar.

It’s a monumental historical feat for a 32-year-old up-and-comer who, in his words, “literally hadn’t made a TikTok before we made Sugarcane.” So, how did this all happen? And what’s even better than Hollywood’s top honour? In this week’s MVP, we chat with the Canadian-American author of We Survived the Night about the best (and hardest) part of his job.

When did you know you wanted to be a storyteller?

I was always drawn to writing. When I was a little kid my mom—an Irish, Jewish New Yorker—put Sherman Alexie books in my hands so I would understand my dad, a Secwépemc, St'at'imc artist who left our family when I was six. I remember writing Alexie-style fan-fiction for a book report. It was a short story set in the future on the Canim Lake rez. I guess I predicted the invention of GLP-1s because the whole premise of the piece was that my people had gotten skinny and were looking back at photos of themselves when they were bigger. That was the whole story.

Filmmaking was something that happened way later when my friend and colleague from my journalism days, Emily Kassie, reached out and asked if I would be open to collaborating with her on a documentary about Indian residential schools. That film eventually became our Academy Award-nominated documentary, Sugarcane.

I now see myself as a storyteller who works across mediums. I really love what I do and I want to do whatever it takes to keep doing it for however long they’ll let me make a living doing it.

What’s the most challenging part of your career?

Doing what I do—telling stories about Indigenous peoples in Canada as well as the United States—you are constantly confronted by the lack of knowledge and interest in our people, our cultures, and our stories. This is especially true in America, where the ignorance is so deep and widespread that it threatens the very enterprise of Indigenous art. We are constantly caught in a cycle of “Indian 101.”

Sometimes it feels like we’re spinning our tires, waiting for society and culture to catch up to the stories and story forms that demand to be told. Add on top of that the ignorance of cultural gatekeepers and the institutions they run. And then add on top of that a broader cultural recession that might actually become a structural thing that puts many journalists, writers and filmmakers out of work permanently, and it all feels pretty bleak. But I try not to get into an apocalyptic doom spiral too often. And when I do I try to remind myself that I am descended from apocalypse survivors.

Could you describe a moment you felt like you’d “made it”?

I think a lot of people would expect me to talk about the Oscars here, but for me the Academy Awards were actually more about seeing my father, my auntie Charlene Belleau, one of my best friends Willie Sellars—the main characters in our documentary, celebrated as the stars I have always seen them as. I will never forget what it was like to see my dad, dressed to the nines with his tuxedo, cowboy hat and eagle feather, strutting his stuff with Ariana Grande in the background. What a beautiful image to get to carry in my hippocampus for the rest of my days.

What does “success” mean to you? Is it as good as they say?

A few weeks back, I was in Whistler at the Whistler Writers festival giving a talk at the Squamish Lil'Wat Cultural Centre, a joint institution run by my grandfather’s people, the Lil'wat, and our neighbours, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh. I was giving a talk below a pole my father carved at the centre, called “Sqātsza7 Tmicw” (Father Land). My girlfriend Joan, who is pregnant, was in the audience alongside dozens of my relatives, including two carloads of family members who drove all the way down from the Canim Lake Indian Reserve across the Duffey Lake Road, one of the most treacherous mountain passes in the province of British Columbia. That, to me, felt for the first time like I was living the life my soul always yearned to live.

Photo by Emily Kassie.

Rosemary Counter is a Toronto-based writer and journalist whose reporting and essays have appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Guardian and others.

Read more from this issue of The Get:

- Is it true that closing old credit cards boosts your score?

- How to get family to stop asking you for money

- Black Friday vs Boxing Day—which sales day in Canada is better for deals?

- Are you paying too much convenience tax?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Get is owned by Neo Financial Technologies Inc. and the content it produces is for informational purposes only. Any views and opinions expressed are those of the individual authors or The Get editorial team and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Neo Financial Technologies Inc. or any of its partners or affiliates.

Nothing in this newsletter is intended to constitute professional financial, legal, or tax advice, and should not be the sole source for making any financial decisions. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Neo Financial Technologies Inc. does not endorse any third-party views referenced in this content. Always do your due diligence before deciding what to do with your money.

© 2025 Neo Financial Technologies Inc. All rights reserved.